Book

Understanding Providence Through Economics

(2022)

Abstract

The science that studies the nature of Divine is called theology. Nowadays, it has become an academic discipline that is taught at universities and seminaries. But other sciences, such as physics, astronomy, and mathematics, also pay attention to the understanding of God. Economics doesn’t stay aside. Today both economists and theologians are trying to develop a new academic discipline, that of economic theology. It has very deep roots. The theory of a just price was advanced by Thomas Aquinas in his works against usury. The economic analysis of Providence comes from Adam Smith's best guess about the market's Invisible hand. The Great Scotsman thought that the Invisible hand was of divine origin.

Economics stays on the border between the social and natural sciences. This is both its weakness and its strength. The most fundamental economic concepts are nothing more than the mathematical expression of human common sense. This peculiarity gives economics some advantages over other sciences in the study of the nature of Providence. Economics cannot discover the sense of divine actions, but it can uncover their workings, when divine actions are explained to people in the literary form of parables.

The basis of economic theory is the model of consumer behavior. This academic field is supported by powerful mathematics, which brings economics closer to natural sciences, even despite the inconsistency of human behavior.

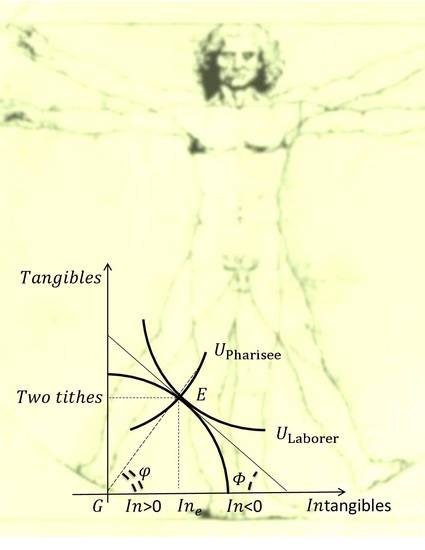

The model of consumer behavior considers the choice between two goods. Here, economics answers the question of to what extent the individual is ready to reduce the consumption of one good in favor of another. But all world religions—Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—ask the same question. To what extent is a person ready to reduce tangible wealth in favor of intangible divine grace?

We cannot correctly measure the intangible benefit of mercy from the Almighty. But economics provides its solution to this problem. The feeling of mercy means that a man has made the optimal choice between tangibles and intangibles. Then, we apply the methodology of optimal consumer choice to the individual who gives up some tangibles in favor of intangibles. Here, intangibles get the correct economic measurement by their opportunity costs.

This scientific concept is nothing more than an expression of common sense. Every Sunday morning, you take a walk in the open air. But once you've read the ads from the supermarket, you’re going there Saturday morning to buy a new microwave at a discounted price. It means that there is an equilibrium trade-off between the pleasure of the walk and the price of the microwave. There, the intangible enjoyment of being outside is equal to the opportunity cost of the discount.

This approach not only expands the field of our analysis, but also makes it simple and understandable. Parents decide to work less, that is, in order to get less tangibles to pay more time and attention to children. Children often understand this and ask for more parental attention and fewer expensive gifts.

Our relationship with God is primarily the relationship between children and their parent. The Almighty gives to people both tangibles and intangibles, waiting in return their righteous lifestyle. However, people’s righteousness doesn’t depend only on their tangibles-intangibles choice but also on the way they make it. Economics can differ genuine righteousness from the demonstrative one. Being demonstrative, it loses its positive value and becomes the hypocrisy of unrighteousness, which we meet in the Holy Scriptures among the Pharisees.

Economics is the only science that can confirm the thesis that "the last will be first and the first will be last." In this way, economics provides a mathematical explanation for the parable of the prodigal son.

We know that the simple language of parables hides their deep inner meaning. Sometimes economics illuminates this depth by paying attention to minor details. So, this book gives quotations from parables in full. It may appear to theologians to be excessive. However, this book is written not only for theologians but also for people who aren't reading the Bible every day but who every day are making economic decisions—to refuel, to buy meals, and to make dinner.

While readers can have different preferences for reading the Holy Scriptures—one can read the Common English Bible, and another likes the King James Version—the author chose for the quotations the balanced New Revised Standard Version, which follows the traditions of both the King James and Revised Standard versions.

The book gives answers to questions why Moses commended to Hebrews to sacrifice two tithes and to return five oxen for the payback of the stolen one. Moreover, economics can confirm in its own way the continuity of both the Old and New Testaments and show that the thesis of ‘other cheek’ does not challenge the thesis of ‘eye for an eye and tooth for a tooth’. Even such a fundamental thesis as "Quae sunt Caesaris Caesari et quae sunt Dei Deo"—render that which is Caesar's to Caesar and that which is God's to God—receives an unusual insight.

The answers to all these questions are set out in this book in simple language. And for a better understanding, they are accompanied by graphic illustrations of simple mathematical symbols. The book is written for common readers who have never studied economics but who understand ideas of value and utility. Deep mathematics is limited here by the derivation of the unique number known as the golden ratio. It is worth demonstrating why Luca Pacioli, the great Italian mathematician and father-founder of modern accounting, called that unique number “Divine Proportion”.

The mathematical proof of the divine proportions of Adam Smith’s Invisible hand has already been published in academic journals. Here it is illustrated in a very simple literary form. The author addresses one of the most famous literary characters, Robinson Crusoe, who ate his food ‘by the sweat of his face’, but his thoughts were “being directed, by a constant reading the Scripture and praying to God, to things of a higher nature.”

Throughout the book, the author is drawing readers’ attention to the prescience in the literal sense of the word of the Holy Scriptures, which intuitively used scientific concepts, such as the economics of opportunity costs and the mathematics of infinitesimals, developed much later. Only this duo can illuminate why the joy over the lost sheep is greater than the joy over the other ninety-nine sheep. And at the end of this book, this duo provides a strict mathematical description of one of the greatest events in human history.

Keywords

- economic theology,

- invisible hand,

- divine proportion,

- holy scriptures,

- parables

Disciplines

Publication Date

Fall November 27, 2022

Publisher Statement

The author has a right to publish this book at BEP.

Citation Information

Sergey V. Malakhov. Understanding Providence Through Economics. (2022) Available at: http://works.bepress.com/sergey_malakhov/36/